Indonesia’s President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo recently called for greater cooperation between Indonesia and Australia in vocational education. Jokowi said such a collaboration would be in line with Indonesia’s plan to focus on human resource development in the next five years.

In recent years Sustainable Skills has had a particular focus on Indonesia, largely because of the scale of the opportunity for Indonesian people. In our experience, there is no doubt whatsoever that a focus on vocational education and training is a fundamental plank in delivering to Indonesians a valuable outcome from improved relations with Australia.

President Joko Widodo has said repeatedly that skills development is a first order priority of his Government and that theme is evident in the policy views of leading policymakers such as Finance Minister Sri Mulyani Indrawati. As the efforts to improve investment and performance on fundamentals such as infrastructure have proceeded, we have noticed a tangible shift in view among Indonesia’s Ministries and State Enterprises – an understanding that Indonesia’s progress and their performance relies on improved skills development. We have also noticed that the Government has looked to Australia – explicitly – as an ally in this effort.

Sustainable Skills has invested two years’ consistent effort in developing in Indonesia an understanding of how quality outcomes can be delivered. The emphasis has been on practical design, careful assessment and assurance and a strong relationship between training and workplace. Australia’s modular, competency-based vocational training system is coupled with strong employer engagement to allow flexibility and practical accessibility to people who often cannot afford a dedicated full time course of study. These principles are now well understood and accepted in both the key Ministry of Research, Technical and Higher Education and in other Ministries and agencies where active vocational reforms are either under way or in planning. Sustainable Skills has driven many of these activities as a partner with the Indonesian authorities and has been directly involved in the formulation of two new centres that will lead change in the Indonesian system. Sustainable Skills has also developed plans to establish an Australian led Indonesian managed training centre which has gained the support of Indonesia’s Government.

In our view Australia has a strategic opportunity to build a link directly with the Indonesian community through support for its vocational training reform. While improved capital flows, trade flows and related material events will go some way to building value in our relations, we believe that the fundamental need that Australia can help to meet is the need to raise broad levels of expertise and skills in that country. Realistically, any effective support will be altruistic in the short term. But the benefits to be gained from a greater level of confidence and capacity in Indonesian society will undoubtedly rebound to Australia’s benefit. Creation of a skills-based link will also inevitably improve the flow of Indonesian engagement with Australia’s broader education system and society. Ultimately, an Australian-designed vocational system in Indonesia is more likely to become by that means a default standard in the wider region, compounding mutual benefit.

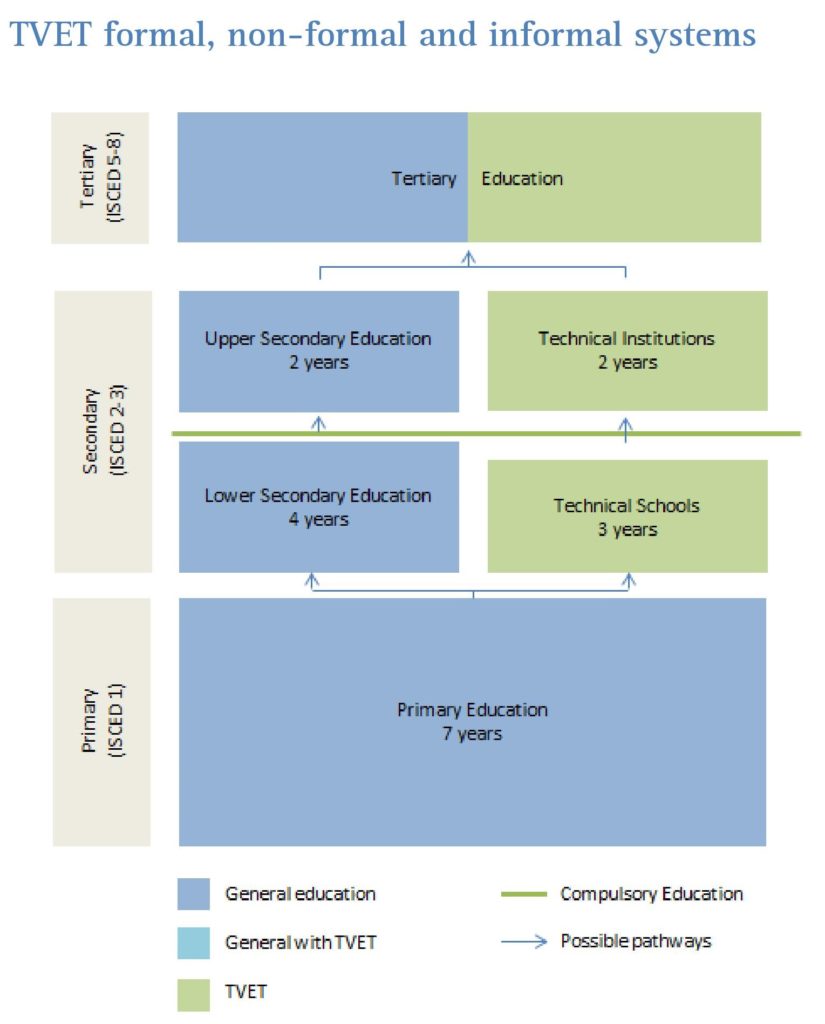

We have observed at close range the two sides of a discussion around Australian engagement with Indonesia on education. In our view it often misses the point of the issue, which is a fundamental need. As President Widodo has said on numerous occasions, the skills issue is a system issue. The point being that it will not be fixed with incremental improvements. Yet in our view much of the discussion about education has focused on the introduction of an Australian college or university to Indonesia or something similar or the recruitment of Indonesian students to Australia or the delivery of online training from Australia which shows a lack of understanding of the challenges facing the Indonesian education sector and in any case it is the broad Indonesian fundamentals – starting at the technical high schools – that must be improved. In any case we do not see a great interest on the part of Australian education and training institutions to invest in Indonesia.

We recommend a focus in the Australian relationship on what President Widodo describes as “human capital”. Initially, this might be a focus of aid and other strategic support that aims to build broadly in Indonesian society a greater capacity to engage with economic and social opportunity. Today’s needs are basic: the skills required to build contemporary standards of infrastructure, operate modern equipment and execute processes to international standards; and the expertise to manage complex technical and conceptual issues in industry and in public sector tasks. Great value can be created if Australian expertise can be conveyed to Indonesians who then go about refocusing Indonesia’s vocational institutions. A simple, yet essential component of that is to demonstrate methods by which industry can be engaged directly to ensure that the value of skills is understood and the quality of education matches workplace demands. Critically, the system delivered must be an Indonesian system, suited to Indonesian needs and its realities.

In our view the development of Indonesia’s broad expertise and skills is a necessary pre-condition to the expansion of relations with Australia. One could see that reality as a handicap or a hurdle; either way it is an opportunity that in our view should be the first priority in Australia’s creative engagement with Indonesia.

This month, I was invited by the

This month, I was invited by the

Last month Sustainable Skills has been officially awarded a consultancy contract sponsored by the World Bank to address skills imbalances and shortages in Uganda. Client of the contract is the Private Sector Foundation Uganda (PSFU) and this is the first non Australian government contract in the history of Sustainable Skills/SkillsDMC.

Last month Sustainable Skills has been officially awarded a consultancy contract sponsored by the World Bank to address skills imbalances and shortages in Uganda. Client of the contract is the Private Sector Foundation Uganda (PSFU) and this is the first non Australian government contract in the history of Sustainable Skills/SkillsDMC.